Understanding Physical Optics Propagation (POP) in Optical Systems

In laser optics, fiber optics, and other biomedical applications, physical optics propagation (POP) is a crucial tool for accurately modeling and analyzing the wave nature of light. Unlike geometrical optics, which only uses rays, POP models the light as wavefronts, offering better accuracy in systems that experience diffraction, coherence effects, and complex beam propagation. In this article, we explore how POP can be used to simulate Gaussian beams, Talbot imaging, Fresnel lenses, and free-space propagation to understand wavefront behavior in optical systems.

Understanding the Wavefront and Physical Optics

In geometrical optics, light is modeled using rays, which are imaginary lines that represent normals to surfaces of constant phase, known as the wavefront. Rays are suitable for fast simulations, but they fail to capture important effects like diffraction and coherence.

In physical optics, light is represented as wavefronts that interact with optical components. The POP model uses an array of discretely sampled points to propagate the beam through optical surfaces. Each surface applies a transfer function, simulating real diffraction and coherence effects.

Why Use Physical Optics Propagation?

While ray tracing is useful for modeling traditional optical systems, POP is necessary in systems where diffraction and interference play a significant role. Physical optics propagation allows for:

- Modeling coherent beams (like Gaussian beams and higher-order modes),

- Simulating diffraction effects accurately (e.g., through finite apertures and lenses),

- Analyzing beam size, phase, and intensity at each optical surface.

Examples of Physical Optics Propagation

Talbot Imaging

Talbot Imaging refers to the phenomenon where a beam forms an image of itself as it propagates. This process is visible in both amplitude and phase modulations.

In the example below, 20 rectangular slits are used to create a diffraction grating. When the light propagates by 20 mm, a phase-reversed Talbot image appears. Propagating an additional 20 mm restores the image.

The POP is setting as below:

The image is not perfect due to the finite extent of the grating. Note the region near the center of the grating has a well formed image.

Fresnel Lens

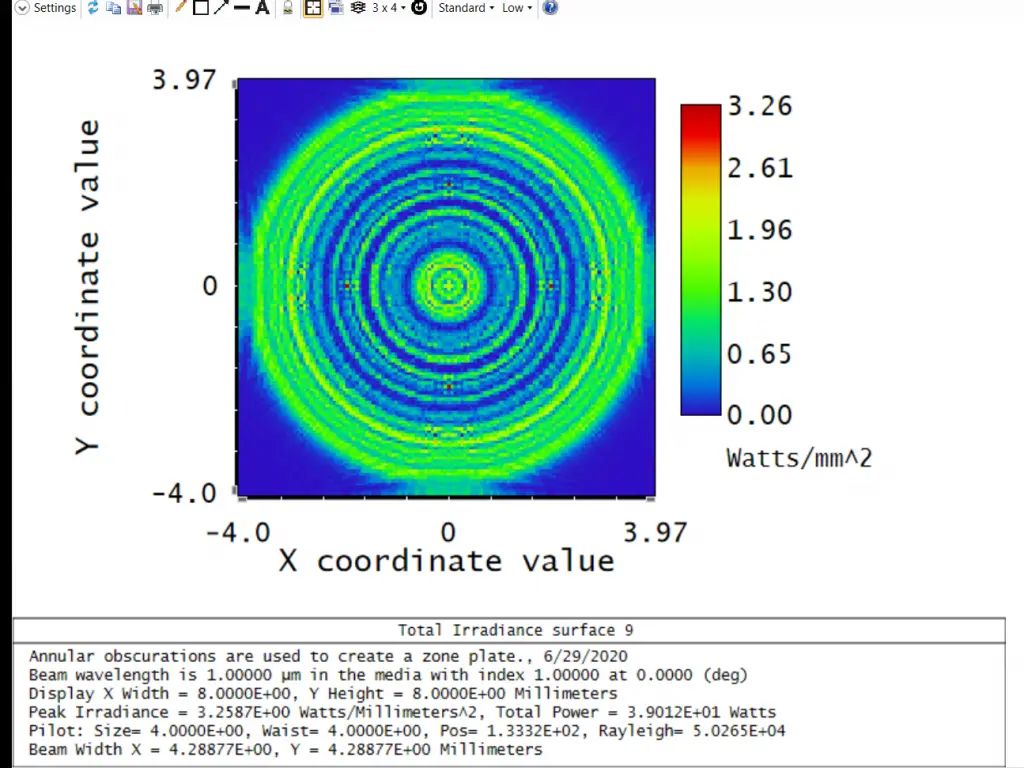

A Fresnel lens utilizes concentric rings to focus light.

Since Zemax does not have a multiple-zoned circular aperture, the zone plate was created by placing one annular obscuration on each of several surfaces; all located at the same plane. The option to “Use Rays To Propagate To Next Surface” is used to speed the computation through all the aperture surfaces.

The spacing of the rings is selected to block light from every other Fresnel zone, so that at a distance of 200.0 mm the light diffracted from all the zones interferes constructively.

The constructive interference creates a bright focused spot on axis; an effect not predicted by ray tracing.

This example also illustrates the intensity of the beam at several planes between the Fresnel zone plate and focus; note the concentric ripples caused by interference from the edges of the zone plate.

Free Space Propagation

The example “Basic Propagation” illustrates the case of a beam propagating through free space. The beam is a Gaussian defined to have a waist of 0.1 at surface 1. The wavelength is chosen to be π micrometers so that the Rayleigh range is 10.0 mm.

At a distance of 1 Rayleigh range, the beam expands in size by root (2), and the peak irradiance drops to 0.5. At a distance of 2 Rayleigh ranges, the peak irradiance drops to 0.2, and at 3 Rayleigh ranges the irradiance decreases to 0.1.

- Note that beam may be virtually propagated backward using the normal Zemax sign convention of a negative thickness.

- Note the phase of the beam along the axis has the correct Gouy shift.

Conclusion: The Power of Physical Optics Propagation

Physical optics propagation is essential for laser beam analysis and optical design, especially when diffraction and coherence effects are significant. By simulating wavefronts and interference, POP gives engineers and researchers the ability to predict and optimize the performance of optical systems more accurately than traditional ray tracing alone.