The quality of an imaging system is often expressed in terms of resolution.

Resolution describes an imaging system’s ability to distinguish fine detail in the object being imaged. The smaller the object detail that can be resolved, the higher the resolution.

An imaging system typically consists of:

- Optical elements (lenses or mirrors)

- A detector (sensor)

- Illumination source

- Electronics and signal processing

Because of this, resolution is not determined by optics alone. It is influenced by:

- Object contrast

- Illumination conditions

- Sensor pixel size and noise

- Image processing algorithms

What Is Resolution?

Unlike focal length or f-number, resolution has no single standardized definition.

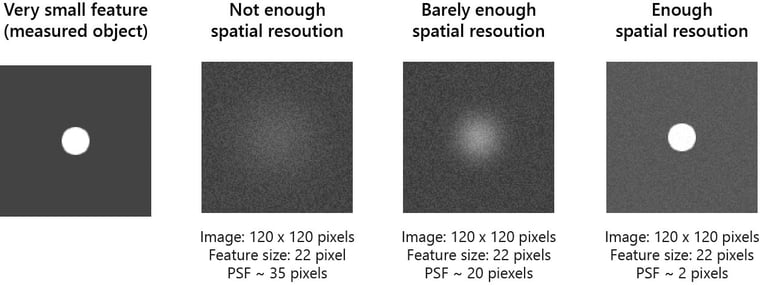

In practice, resolution is defined as the minimum separation between two features that can still be distinguished as separate.

Resolution can be expressed in two equivalent ways:

1. Spatial-Domain Resolution (Distance or Angle)

In the spatial domain, resolution is defined as:

- A distance in the image plane (e.g. microns, mm), or

- An angle in object space (e.g. arcseconds)

It corresponds to the smallest separation at which two point objects are still discernible.

This behavior is often illustrated using image irradiance vs. position plots, where two overlapping intensity peaks become distinguishable only when sufficiently separated.

2. Spatial-Frequency Resolution (lp/mm)

Resolution is very commonly specified in the spatial-frequency domain as:

Line pairs per millimeter (lp/mm)

For example:

- “The system resolves 100 lp/mm”

- This means the system can distinguish features separated by: 0.01mm=10μm

Higher spatial frequency = finer detail.

Diffraction-Limited Resolution and Cutoff Frequency

For a diffraction-limited optical system, the cutoff spatial frequency (ν0) is given by:

ν0 = 2NA/λ

Where:

- λ = wavelength (mm)

- NA = numerical aperture of the lens

Key implications:

- An optical system cannot transmit spatial frequencies higher than ( \nu_0 )

- Shorter wavelengths yield higher resolution

- Larger numerical aperture improves resolution

- This represents the absolute physical limit imposed by diffraction.

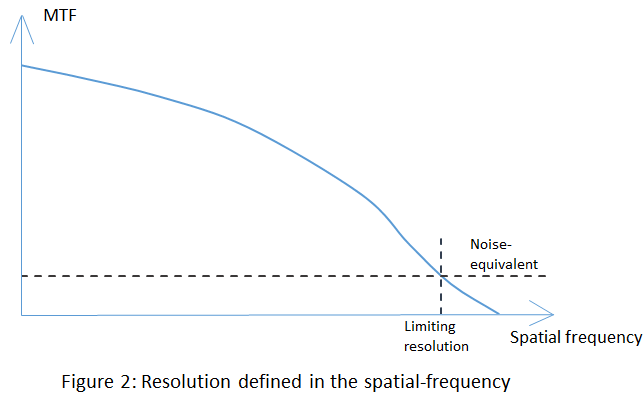

Resolution and MTF (Modulation Transfer Function)

In real systems, resolution is closely tied to the MTF.

Each component in the imaging chain contributes to the overall system MTF:

- Optics

- Sensor sampling

- Pixel aperture

- Noise and electronics

Resolution is often defined as:

-

The spatial frequency at which MTF drops below a specified threshold

-

e.g. 10%, 5%, or noise-equivalent modulation (NEM)

-

This approach connects contrast and detail visibility, which aligns well with human perception and machine-vision requirements.

Why Resolution Is Often Used Instead of MTF

MTF provides a complete performance description, but:

- It is a function, not a single number

- It can be difficult to compare quickly between systems

Resolution, by contrast:

- Is a single-number specification

- Is easier to communicate

- Is commonly used in system requirements and datasheets

However, resolution alone cannot fully describe image quality—two systems with identical resolution may have very different contrast performance.

Practical Ways to Measure Resolution

Common resolution measurement methods include:

- USAF resolution targets

- Slanted-edge MTF method

- Point-source or pinhole imaging

- Knife-edge or bar-target analysis

The appropriate method depends on:

- Imaging modality

- Field of view

- Signal-to-noise ratio

- Application (visual, machine vision, scientific)

Key Takeaways

- Resolution measures the ability to distinguish fine detail

- It can be defined in spatial or spatial-frequency terms

- Resolution depends on the entire imaging system, not optics alone

- Diffraction sets a fundamental upper limit

- MTF links resolution with contrast

- Resolution is convenient, but incomplete without MTF

Understanding resolution properly is essential for designing, specifying, and validating imaging systems.